By Caleb Allison

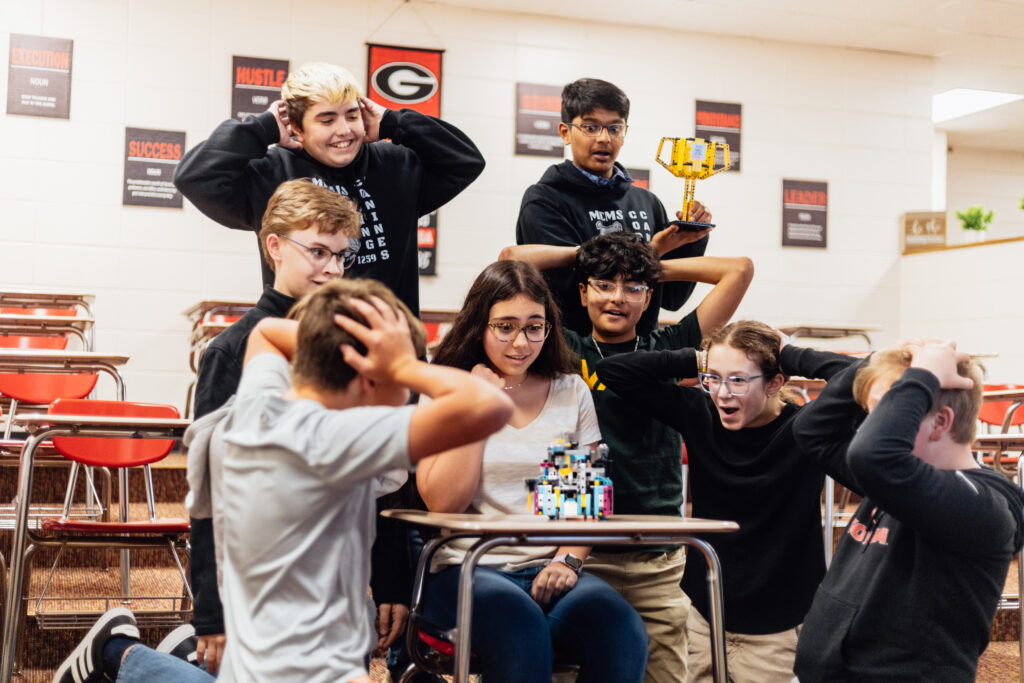

The Coding Canine’s Team at Monroe County Middle School.

At first glance, it looks like a typical after-school robotics club: middle schoolers in matching shirts, laptops open, gears clicking, voices bouncing across a cluttered classroom. But if you look a little closer, you’ll see something rare—a team that’s not just learning how to build machines, they’re learning how to build trust.

This group of students is Monroe County Middle School’s Lego Robotics Team. They go by the name Coding Canines. And in their current state, they’re the culmination of a season defined not just by engineering, but by evolution.

Coaches Adair Woodward and Morgan Glover remember day one clearly: the students barely knew each other. Many were new to the school. Few had experience with coding or robotics. There were awkward silences, uncertainty, and a lot of coach direction.

“At first they came to the coaches,” Woodward said. “But it took maybe a week before they had inside jokes and became close. Before long, they started to handle things themselves because they knew who could do what better than the other.”

That early dependence turned into something else. Communication improved. Confidence grew.

These days, they solve problems together, often before a coach steps in. That kind of trust is hard to build—especially when you’re performing in high-pressure competitions.

That teamwork is what earned them state recognition, where they won first place in the Core Values category. For context, that award doesn’t go to the fastest robot or best design. It’s given to the team that exemplifies inclusion, respect, teamwork, and spirit.

Woodward said it was her proudest moment—not because it was expected, but because the team genuinely earned it.

“A lot of teams win because, to be blunt, it’s cute seeing kids build robots. But these kids won because they showed true collaboration toward a shared goal. That’s something the world could learn from.”

When it came to technical development, the growth was just as real. “Not many of them had experience with coding in August,” Woodward said. “Now all but one can handle it on their own.”

Even the ones who started out hesitant found their footing. Everyone gained working knowledge of the tools and systems powering their robot. And while the learning curve was steep, they climbed it together. That peer-to-peer learning became one of their defining strengths.

A key part of that growth came from how the coaches coached. They didn’t hand out answers. Even though they knew what the judges wanted, they resisted the urge to step in.

“I ask questions,” Woodward said. “‘If you need to do that, what could you use? What if we turn this part that way?’”

By encouraging curiosity over instruction, students began asking better questions—of each other and themselves.

When asked to freeze one moment from the season, Woodward paused. There were a few contenders.

One was a photo from the state competition. The team had just finished competing. They were wearing bright blue shirts, and one student, Drew, was lying on the floor making everyone laugh. Another came later, when the team found out they’d placed fourth and would be advancing to nationals.

The students say robotics feels different than school.

“In class, you just work with people for an assignment and you’re done. But here, you work with the same people for eight months. It feels like a job.”

That kind of time builds more than knowledge. It builds work ethic and real collaboration. A sense of shared purpose. These students are learning skills that will carry them into adulthood and into careers that can and will change the world.

When asked what their secret weapon was, student Christian Burgand answered without hesitation. It wasn’t the robot. Not a specific part. Not a program.

“It’s our rhythm. We’re synchronized on and off the table, cheering each other on.”

He referred to their table run, the two-and-a-half-minute stretch where a team sends their robot across a table to complete as many precise, timed tasks as possible. It’s the high-stakes moment every competition builds to and the Canines approach it like choreography. Practiced. Unified. Calm.

Outside of the robotics missions, the team also tackled a major innovation challenge: from what I gathered, they were asked how to help oceanographers protect their data buoys from iceberg collisions. The students interviewed a real oceanographer and designed a collapsible, origami-inspired system to shield the sensors before impact.

“Their buoys are collecting iceberg data, but something keeps knocking them loose. When that happens, they lose everything,” one student explained. “So we designed a system that could protect the sensors.”

That solution was imagined, researched, and presented by middle schoolers, and it seriously impressed the judges and elevated their overall score.

At the end of our conversation, I was impressed and honestly a little envious. I asked each team member where they hoped robotics would take them. The answers varied: some want to design prosthetics, others hope to go into aerospace or mechanical engineering. One even said veterinary medicine, with robotics involved.

“If even one of them goes into STEM because of this,” Woodward said, “it’s all worth it.”

This isn’t just a robotics team. It’s proof that when you give students time, trust, and a challenge, they rise. They figure things out. They build more than robots. They build each other. And they’re just getting started.

Thanks again to Anderson Barrett, Andrew Morris, Caleb Keenan, Elizabeth Goode, Niyam Patel, Ansh Patel, Hunter Dickerson, Christian Burgand, and Sophia Larrick. You all are incredibly inspiring.